Designing Urban Agritecture: An Interview with Chicago Architect Martin Felsen

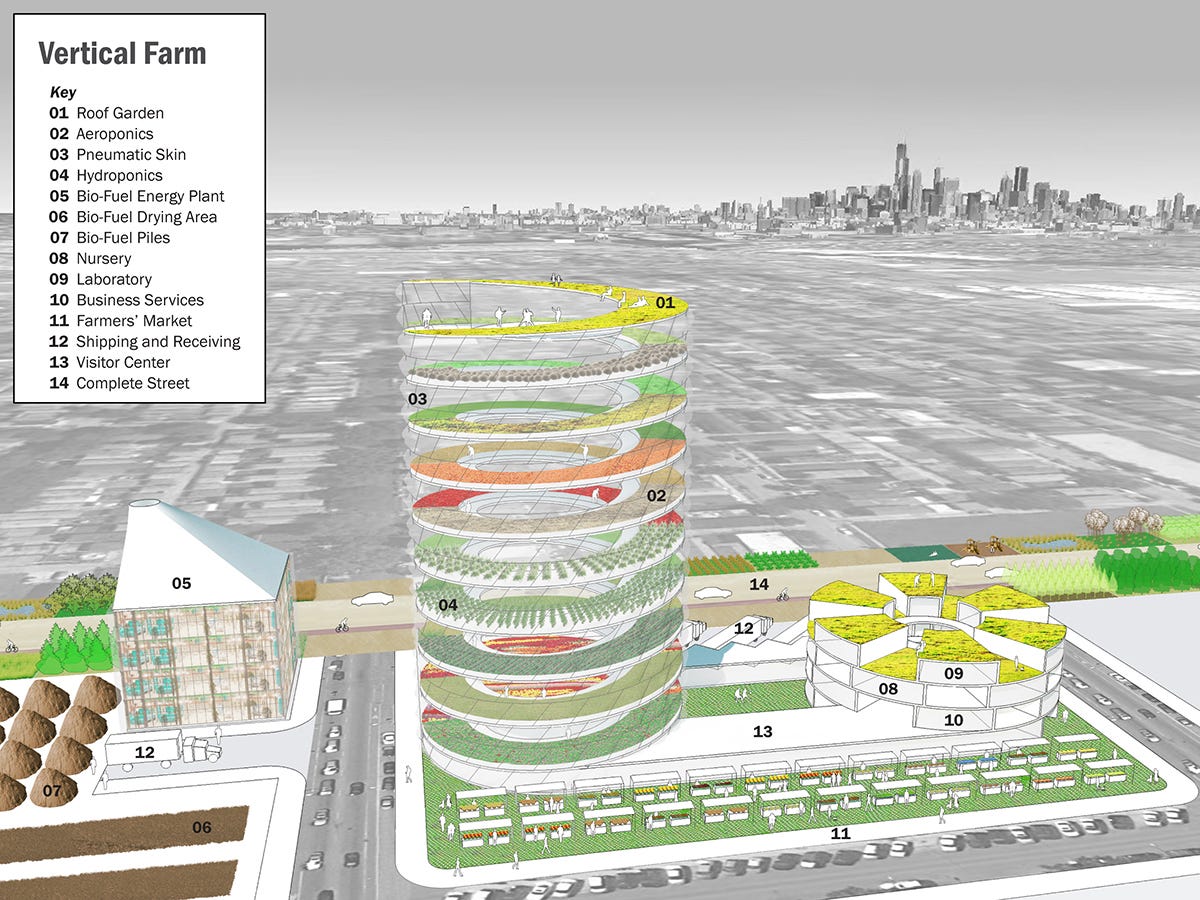

When researching the viability of vertical farms, I came across a truly beautiful plan for the City of Chicago produced by a Mayoral Task Force convened in 2011.

The Chicago Vertical Farm Task Force identified four vertical farm models that could be built, are being built or are already built in the Windy City. The design proposals listed potential partners, a description of energy sources and some project plans.

Model 1: Vertical (Production) Farm

Model 2: BioTech Incubator

Model 3: Edible Greenroof

Model 4: Renovated Commercial Building

For all the vision in the report, however, very little has changed in the city over 10 years later. Today, of the identified models, there are only a some “edible greenroofs” (rooftop gardens) and a handful of renovated commercial buildings with productive indoor farms. There has been an improvement, but it’s not exactly the growing revolution city officials theorized.

We have the vision, we have the technology, what is stopping these urban-ag features from taking root? Pun intended. To learn more about urban agriculture, Martin Felsen, an architect on the 2011 Chicago Vertical Farms Taskforce, was kind enough to share his insight on the industry.

Growing features in apartment designs are, at present, only viable for luxury builds, and often are a dream that doesn’t reach reality, according to Martin. As he pointed out, “we've done some designs for other vertical farm projects– none have been built. That’s typically what happens.”

The energy required for light and water features that make hydroponic farms work are considerable, and without energy abundance, it’s tricky to figure out how to make such a feature work in an affordable, new building. Rooftop gardens with access to rain and the sun are more feasible, as are other more localized growing stations.

Portable mini gardens or leafy green growth stations are popping up on the commercial market, with small setups selling on Amazon for around $70 and larger kitchen units ranging between $600-1000. These insertable features, although still a luxury kitchen addition, may be the first steps towards food growth integration in the average American kitchen – an appetizer before larger food production features become more standard.

It may seem like a far off dream, but consider that the washing machine was once considered luxury good for those with electricity, but between 1930 and 1945 it became a standard appliance in a middle class household– something almost unthinkable less than 30 years before.

Reasons for optimism

Martin said that any architect would love to design a dynamic building with food production features involved and that it’s a topic that comes up often in the field. “We all want to design one of these things,” he said, but progress is slow moving. Martin suggested that universities or K-12 schools might start adding vertical farm features to dining halls or cafeterias, with the aim of adding marketability to the school.

Some highlights from the interview:

“Community organizers and urban agriculture people said that they viewed vertical farming as the corporatization of their activities, that they had no interest in talking to or dealing with the vertical farm community, which is mostly made out of real estate professionals, or investors, because they felt as though they were co-opting their projects, their communities…if someone built a vertical farm in their community, they would view it as a gentrification project

“Singapore is a country that has to import almost everything that they eat…[and] they were trying to get away from that. So vertical farming was a solution to getting themselves out of some relationships and producing what they needed.”

“People understand that their personal carbon footprints have so much to do with the garden's travel– those transportation miles and up.”

Check out the full transcript below!

An interview with Martin Felsen, an architect for UrbanLab in Chicago.

Patricia: I came across a very beautiful vertical farming plan that you guys did for the city of Chicago, have you been approached to do a similar report for another city since then?

Martin: We've done some designs for other vertical farm projects– none have been built. That’s typically what happens, in the United States anyway.

There are many vertical farms built outside of the United States, and I've been to a couple of conferences where the Asian communities and European communities are showing their vertical farms, showing pictures of their buildings, local farms.

Meanwhile, Americans are just talking about it, trying to understand how to get them built. Trying to understand the relationship between the capital costs and the return on investment, which is very difficult. And so we've designed a few, but none get built, at least that we've designed.

So, yes, we've made some reports, we work with clients, but we haven't had any success getting any built.

Patricia: So what do you think are the biggest challenges in America, or the biggest differences between here and other countries?

Martin: The cost of growing food in the United States is very inexpensive. Traditional agriculture doesn't require inputs of electricity because the sun is available for exterior farming, there are often low water inputs because there's enough rain or because water is so cheap in agricultural settings that that's not an input cost either.

Also, land is cheap and available and it's a pretty straightforward practice of farming.

Now this is totally contrasted to a place like Israel, which has very little farmland, and it's incredibly expensive to farm there, or in places like in Asia, or other places around the world. So it's just a lot cheaper to grow food conventionally, or traditionally, in the United States.

The cost of electricity is very high. The cost of water is very high. The cost of sewer drainage is very high. And all these things make vertical farms not a worthwhile investment. Right now, at least in the U.S., it seems like.

Patricia: Chicago didn't move forward with the vertical farm plan that they thought that they maybe could have ushered into existence in the late 2010s. However, there was a pretty big push for more community farms, and more like urban farming. Do you, do you see community farms as a compliment, or do you perhaps think that people are gardening more because vertical farms aren’t an option.

Martin: I thought they were complementary until I wrote that report…. to take a step back, that report was produced through a workforce, a team of people that the mayor in Chicago put together for several conversations. There were people working at the community level in urban agriculture, there were also real estate investors interested in vertical farming, and there were a lot of technology companies, people supplying energy, lighting like super efficient electrical lighting, water savings, technology– all of those people.

Anyway, I went into this project thinking, “Okay, the first step is connecting to the community, urbanized culture, and that will lead in a complimentary way to vertical farms.”

But the community organizers and urban agriculture people said that they viewed vertical farming as the corporatization of their activities, that they had no interest in talking to or dealing with the vertical farm community, which is mostly made out of real estate professionals, or investors, because they felt as though they were co-opting their projects, their communities.

For instance, if someone built a vertical farm in their community, they would view it as a gentrification project, essentially. And so there was a lot of antagonism on both sides.

Patricia: Do you think perhaps in future vertical farms might be a selling point for an apartment building? Do you think the real estate space is moving that way?

Martin: Yes. I do think it is going to be a luxury market more than the everyday market, which is the problem, I suppose. And there are some interesting examples of – I wouldn't call them vertical farms – but industrial production farms. In Chicago, there's probably between 5-10 of them.

There are different ways to categorize them. They are usually one-story buildings in old manufacturing warehouses or something like that, and they often have a really interesting loop of products. For example, there might be fish or chickens who produce waste that serve as fertilizer for these small farm loops.

My favorite production facility like that in Chicago is a giant warehouse owned by the Method company.

The whole roof, which is giant, perhaps 100,000 square feet or something crazy like that. It’s operated by an urban ag company – they sell a lot of food to Whole Foods – but I wouldn't call it “vertical," even though it's somewhat-vertical.

It's definitely a value add to Method because the company gets to talk about their sustainability – and that's exactly the mindset of higher end residential apartments that will eventually incorporate urban agriculture into their designs. It’s an interest in the environmental footprint similar to what we see from corporations.

In fact, I think that [vertical farms in residential buildings] have probably already been done. I walked through an apartment building in Tokyo not too long ago, right before the pandemic – it was a mixed use building. A sea of commercial stores, and then one story of residential space, but at the top of the building was an urban ag installation and a restaurant. It was really cool. So there are concept samples of buildings like that around the world.

Patricia: Have you seen higher end homes, or people that like innovative design, wanting to have more growing features in their kitchen? Or restaurants wanting plant features in their space?

Martin: Yeah, absolutely. We've designed a couple of residential projects where it's exactly that – we usually call it a greenhouse, but it also has some production value.

It's about lifestyle – being able to go into a greenhouse, get some fresh oxygen while still in Chicago, in the middle of winter. But, it's a total luxury product.

Patricia: I think there are a couple grocery stores that have a vertical farm feature in Florida, like Krogers. Do you have a feel of where in America you think these designs will start popping up?

Martin: Friends of mine and I talk about this sometimes, because we're just fascinated by building technology, and we all want to design one of these things.

We think, perhaps, a rich city like Chicago is a possibility. [The Northwest] Amazon headquarters built a huge greenhouse food store, but it's not a production food facility. It's more of a room with a huge greenhouse breakroom room, or something like that.

It’s not a viable business anywhere in the United States. When they get built, slowly but surely, it's going to be more [of a real estate feature], which is a value add from a marketing point of view.

In New York City or Los Angeles or Chicago, [this feature] will eventually get worked in, but not in any real way. A five-star restaurant at the base of the building will be the one utilizing a vertical farm, and there will only be super high-end stuff in it. Plants that normally cost $30 a pound, or whatever is super expensive to grow and ship.

Patricia: There is some proof of concept. They're kind of expensive right now, but it's almost like a mini refrigerator or like a counter farm that just regrows lettuce quickly under a light. Do you think that as technology becomes cheaper, will we be more willing to accept these changes?

Martin: Yeah, that's true. It’s so hard to tell because, as we've seen, what people are most interested in is convenience. And, from what I can tell, people in your generation [Gen-Z], they just want something that they can order, you know, through an app and get it immediately.

I have, for example, a little aquaponics station in our kitchen – it's a fish tank. On top of the fish tank, there's different greens that grow. It takes a lot of labor. It's really hard to operate, and I'm not sure the next generation of consumers wants more work or less work. I would always lean toward less.

I'm not convinced that anybody alive today is interested in a lot of labor when it comes to food – I think just the opposite. But, there might be a whole group of people out there that have no idea about who are willing to do a little farming on their own.

Patricia: What are some advice for people in mid-sized to smaller cities who would be interested in attracting vertical farms? What are some things that their city planners or city councilors maybe don't consider?

Martin: Some cities certainly advertised lifestyle amenities. So, Portland and other places that are next to mountains, or next to beaches, can certainly claim that they have some kind of natural resources to attract younger people or to attract a certain group, which is really important to every city.

And cities compete quite seriously for young talent. But, the problem with the vertical farm, at least the vertical production farms is that they're so locked down and security driven because they have a multi-lock vestibule system, and one entrance and exit. It has no pathogens, bugs, insects, germs, everything has to be wiped clean before entering or exiting these things.

It's not like it is a tourism-thing or a recreation-thing. It's like the back of a grocery store, and no one is allowed back there. So I'm not sure if it can contribute to the competitive advantages of any size city.

For instance, there are cities in Southern Canada that grow a lot of tomatoes that we eat and they have just acres of hothouses. Those are all locked down. Nobody interfaces with those things. And even to get into one, you have to have special permission. I remember when I visited a “vertical” farm, some of it was again, gardens, one story on top of the building here in Chicago at the University of Chicago – the permission that I needed to get into there, even though it was amazing, was so extreme that I'm not sure that it is going to be a good formula.

However, we were just talking to somebody today who is interested in and who bought land in New Mexico and wants to build what's basically an agricultural-oriented district.

It's a farm that people would rent cabins and vacation in for a week, or two weeks, or something. They would go there and work on their vacation, or play on the farm, and that would be part of the adventure. I can see that as a possibility.

But again, it's more of a luxury market or at least an upper-end market where people have to have money to participate in. So, I'm not and we've had a lot of conversations like that with people.

Patricia: Do you think there's a pretty big appetite in the like architect and design community for these types of projects?

Martin: Oh yeah, absolutely. There's been a lot of demonstration projects, lots of designs, lots of ideas because it taps into two of the more, more dynamic trends in architecture design, one being sustainability for agriculture, ecology, the other being tall buildings. Somehow connecting those is what a lot of people are dreaming of.

Thinking back now in some of these meetings and conferences, I think Singapore had some really good examples. Singapore is a country that has to import almost everything that they eat, and they still probably import a lot of food and a lot of water from some countries that don't necessarily love to have trade relationships with – so they were trying to get away from that. So vertical farming was a solution to getting themselves out of some relationships and producing what they needed.

Patricia: I feel like a vertical farm, or like a type of farm feature in a building, is the next phase of community food interest. Do you feel like people want more of a personal connection with food?

Martin: Yeah, I think it's exactly what it is. People understand that their personal carbon footprints have so much to do with the garden's travel– those transportation miles and up. Also, there's a kind of security to buying things locally that gives people a good feeling.

Patricia: Was there anything else from the process of producing that report and working with the city that you learned?

Martin: Actually, I haven't even read that report in years. Just thinking back on those meetings, I think the main thing I learned is that there's just no return on investment right now. We've talked about that already a little bit, but I doubt it's going to happen. It's going to take a long time for that to be the case.

This country is rich with agricultural land, and that's going to prevent vertical farming from coming to fruition. There would be a bunch of minor scale examples, one offs and a lot of urban projects, just not a lot of not a lot of vertical-looking farms.

I've sampled a lot of food grown locally and on urban farms. And it usually does taste better because it's not made on an industrial scale. And oftentimes people are using heirloom seeds and things like that that are just better. Tomatoes are an example that most people know.

There is a market for these ideas, and what's been developed so far, but it's such a high end market – imagining those ideas trickling down to the other 99% of us is just hard to imagine.

Check our Martin’s design firm here: https://www.urbanlab.com/about

Further Reading:

Creating Sustainable Food Systems with Trademarks and Technology, by Agnes Gambill West.

Farming Abundance | Phony Demand and Underpopulation: Problems Plaguing American Farmers By Matthew Yglesias

Zoning Policies Intended to Support Agricultural Abundance Are Failing, By Emily Hamilton.

Cultivating The Farm-Startup Ecosystem: An Interview with Farm Entrepreneur Brian Caroll, by Patricia Patnode.

Book | Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities by Alain Bertaud