Demonstrability has always been important to farmers. Before adopting a new tool, they need to have confidence that the expensive equipment, seeds and other tools they invest in will only increase yields and field productivity. Brian Caroll, Director of Grand Farm in North Dakota spoke to me about this need for confidence,

"There's a lot of noise, especially around technology, in terms of the different claims that happen. And from a grower perspective, what they're looking for is something that's simply going to improve their ROI[return on investment]. And if it works, if it can be demonstrated, they will incorporate it, but it takes a while for that adoption of technology to happen. [But]By the time it gets to the grower, it has to be really, really verified, trusted.”

Recognizing this market opportunity and capitalizing on the desire to innovate, successful farm software entrepreneur Barry Batcheller decided to sniff around North Dakota for new and interesting ideas. It makes sense that those best suited to produce farm tech innovations are those who are most familiar with farms and that was who Barry was looking for. Brian described how Barry asked a room of growers and inventors, “In this region, if we ever declare our major to the world, what would that major be?”

That question was the catalyst for Grand Farm, which Brian describes as their “thesis.”

Grand Farm then talked to farmers and identified operational pain points, while recognizing that “agriculture is different from other industries..the feedback loop isn’t as fast. It’s kind of constrained by the growing cycle… It's isolated, it's fragmented.”

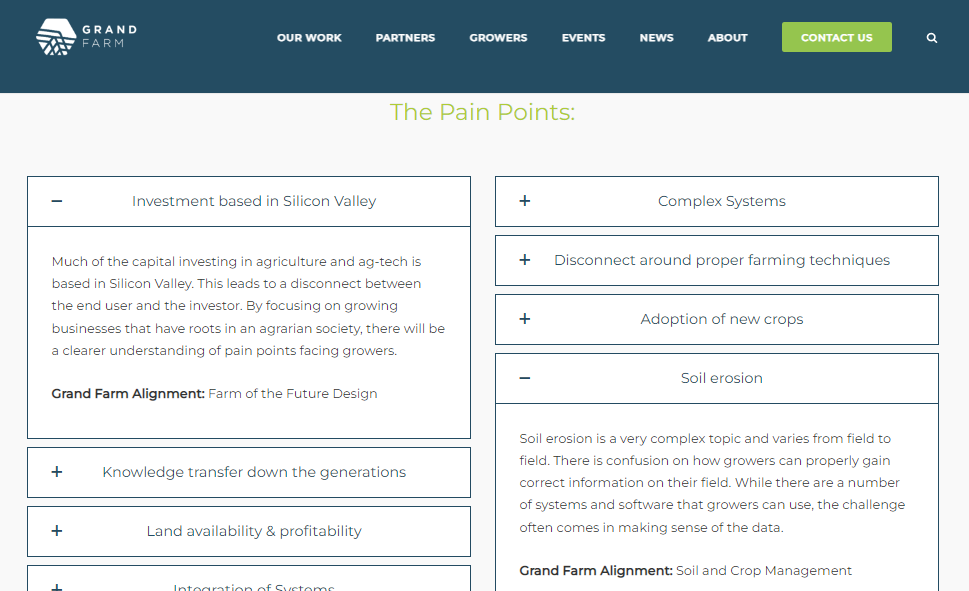

Some highlights from Grand Farm’s 2020 Pain Points Report:

In response to these pain points, Grand Farm created an ecosystem to connect farmers to technologists, and technologists to each other to build credibility and demonstrability for capital investments. Brian and his team also started the first coding academy in North Dakota to meet the industry demand they are generating. Grand Farm is continuously working to improve feedback loops between consumers, farms and engineers because according to Brian, “The need is around efficiency. And if autonomous systems will create more efficiency, that's where that adoption will take place.”

Grand Farm is hardly a solo operator in the region. The farming Renaissance is underway in Fargo, North Dakota. While slightly more humble than Silicon Valley, ag startups have nestled into pockets of space in downtown Fargo, giving them the ability to conduct experiments in fields and warehouses nearby.

Inspired by the concentrated success of Silicon Valley, some state governments have tried to centrally plan their own innovation hubs. The federal government has aided these ventures, allocating $500 million last year towards the designation, planning and implementation of regional tech hubs. But top-down efforts to create innovation haven’t quite achieved the grassroots success of Fargo. These well-intentioned investments naively miss the obvious truth about innovation —it cannot be kickstarted with government dollars and can only occur through disruptive entrepreneurship. New industry ecosystems are ever-changing and often messy. Even Silicon Valley doesn’t have the same landscape that it did 10, or even 5, years ago. The only way to create innovative tech hubs like Silicon Valley and Fargo is to let them develop, fail and adjust based on the needs of the region and of the larger market.

It’s unlikely that that government would have picked the Peace Garden state as the next great innovation hub. But the subtext of Brian’s interview with me is “Why not here? Bright minds attract bright minds, and we can improve the world.” Beautifully optimistic and not too abstract, check out the transcript to hear about their operation model and learn about how growers are farming for the future.

Full Transcript of Interview with Brian Carroll, Director of Grand Farm in North Dakota.

Lightly edited for clarity.

Patricia: Are you very involved in day to day management or is it mostly oversight and processes?

Brian: It’s a small organization that we have. So I would say yes to both.

The team that we have is fully dedicated to the ground farms, and then we work with other parts of the Emerging Prairie organization like marketing and operations, finance and things of that nature. But, it’s really gaining momentum now. But the reality is…all aspects of it.

Patricia: Is Emerging Prairie the main funding source, and they fundraise for you guys, or how does that work?

Brian: Well, let me give you a little bit of a context. Emerging Prairie has been around for about ten years. Emerging Prairie’s initial mission was to connect and celebrate the entrepreneurial ecosystem here in the region. There's a series of events and programs that we would do, and also host some national ones, like Fargo TenX. We would bring in Prairie Capitol summits events, for example, where we would bring the venture community in with the entrepreneurs. It was really about creating an ecosystem, a network and developing opportunities for them to grow and flourish.

The Grand Farm initiative came out of one of those events. It was at an event called, “1 Million Cups,” in which one of our entrepreneurs, who’s pretty famous in the local area, Barry Batcheller. He was responsible for putting the first computer chip on a combine…

And at this event, at 1 Million Cups, he went on stage, we had about 350 people there, and he asked, “In this region, if we ever declare our major to the world, what would that major be?”

So, he asked the question, and then at Emerging Prairie we brought a group of leaders together and we tried to identify what our major would be. We landed on the Grand Farm, and more specifically, advanced technology and precision agriculture.

And that became our thesis.

Patricia: How autonomous is the farm?

Brian: So, when we first started and brought people together, we put together a moonshot. We were calling it our BSAG, our Big, Scary, Audacious Goal. We wanted to create the first fully autonomous farm by the year 2025.

Since then, we realized that that technology is already out there. There are activities that are underway, and that idea became less interesting for us.

The Grand Farm User Story

What we've done is we've created our “Grand Farm User Story,” which takes place from the time that a farmer plants a seed, all the way to when the consumer eats the food, and that whole value chain and supply chain—the ‘in-between' is our story.

We’ve created a series of projects that function as chapters within that user story.

Chapter 1 Soil Health

One of the projects that we really focused on was soil health. The main reason for that is because our first partners at Grand Farm were really interested in that research. North Dakota State University, CHS, really wanted to do that research, so soil health became a big part of what we did.

Chapter 2 Farm Sensors

The second theme, or chapter that we had, was really around all the sensors that are out there—the Internet Of Things and the ability to take that data, to visualize it and to make insights. There's a lot of companies and organizations that are involved with that. So that became another chapter of the project.

Chapter 3 Autonomous Systems

The third is autonomous systems. There's a lot of time-systems out there, but in many respects they're fragmented and they're isolated from each other as well. So we have technology on the farm that is autonomous, but the projects are:

How do we connect with organizations?

How does data insights inform a track that a tractor would take?

Chapter 4 Farm of the Future

Our fourth chapter, that we've really focused on, was the farm of the future. The future, more specifically, and what the infrastructure needs to be and what are the power sources that go into it.

What do the connections need to be out on the farm?

There's a lot of companies and organizations that are focused on that.

Chapter 5 Improving the Human Condition

The fifth and final chapter that we focused on was improving the human condition. The ability to advance technology, within our network, that could get into the hands of an end user, perhaps someone in Africa or India. ‘What to do in order to really advance that technology?’ is another series of projects that we are starting to split up.

We took this Grand Farm user story, we bought each of these different components together, these chapters, and we started doing projects. And the projects came from our partners.

The first year, we had 3 or 4 partners that were involved, now we have over 70. It's really the interest that our partners have, driving [the growth] and producing the projects.

It's important to note that we are an open and neutral platform—we want to have everyone involved in that innovation, and we create projects designed to establish feedback for each of these different groups.

Patricia: What's been the most impressive project to you that you've worked on so far?

Brian: My favorite project right now—we evaluate the success of our project based on how much we drive engagement with our partners—is a project called Harvest Trace, in which we are taking a look at how a soybean goes through the supply chain. So, the bean is traced from processing and all the way to the consumer.

The reason why that project was exciting is because 13 partners were involved with that project, and we were able to develop meaningful relationships between partners within that supply chain that may not have had exposure to the data that they were working with, and then they started doing projects and some business together as well.

So, we became the facilitator around the project, in order to drive that engagement, and that project covered so many different potential partners that it was really fun to watch that grow.

Patricia: Have you guys worked with any Ag. drone companies to do experiments?

Brian: We have, in fact, one of our first partners, I would say our first partners were drone companies. And then over here in North Dakota, we have a close partnership with the Northern Plains test site. The state is rolling out Vantis (drone system), as well. So, there's a lot of activity around that. A lot of drone companies are coming into the state as well, and the farm becomes part of that.

Patricia: Do you do summits, or mentorship, or tutorials for farmers in the region to learn how to adopt tech?

Brian: A little bit. We have our ecosystem, and we have our projects. The ecosystem is designed around a series of events and programs that bring partners together. We do major conferences. There are three signature conferences that we do. The first one is SpaceAg, and we look at a lot of technology, like vertical farming—things that NASA is interested in, a lot of startup activities. Our second conference is called Cultivate, which is designed to match-make the growers with people in the technology industry. So, we bring a lot of growers, match them with technology and they create these feedback loops.

The third major conference that we have is Autonomous Nation, and that's designed to bring together organizations that are involved with autonomy. There, it’s important to be able to see that and to demonstrate that [autonomous capacity and partnership].

As we think about our ecosystem, as we think about these conferences, there's really four primary groups that we serve. The first one is industry partners. Industry partners are either digging for technology to help with their own organizations or they have great technology and they're looking for ways to or to amplify and demonstrate that.

The second main group that we work with is startups. There are a lot of startups that are sitting on top of one of the pain points. They have a solution for it, but they're looking for capital, they're looking for customers, they're looking for an amplification of their work.

The third group that we work with as universities. These universities often have amazing research, but the challenges that they have is how to connect with the industry in a much more direct way, and more specifically, how can they start to commercialize that research into applied applications?

The fourth group that we've really focused on, and we've put in the middle of all this innovation, is the grower. Making sure that the grower is tied into the innovation. What we do through our project is create event programs that bring people together and then projects that engage them in a meaningful way, in order to drive feedback loops between each of these different groups.

Patricia: Have there been any USDA grants or programs that have been particularly helpful?

Brian: We work with the USDA and also the agricultural research services around a lot of the ecosystem stuff. And what we like about those programs, is the ties with the USDA, and also with our local university NDSU. We do specific projects around those, and that ties us together in a real strong and meaningful way. Grants are a big part of what we do, and we're pretty competitive with them, especially as they become available. But, the thinking that goes into the projects are probably the most important things.

Actually, at Grand Farm, after the major was declared, we found out about a Small Business Administration grant that was around regional innovation clusters. We found out basically 4 days before the due date. So, we put together a proposal for it, and that’s where our strategy came out.

We identified three pain points we wanted to solve, and those were things that were very specific to this region. So, lack of venture capital was a big one. Lack of a scalable workforce was another because we're going through a digital transformation in agriculture. The third was farm safety, and the one that everyone kind of identified was that we have to get much more efficient in agricultural practices in order to feed 10 billion people, and to do that sustainably.

We identified those big pain points and those big challenges. And then we developed a 5 year road map around the Grand Farm.

Right in the middle of the strategy was the ecosystem we just described, events, programs, bringing people together. Connecting to thought leaders.

The second piece of it was the innovation platform, how we bring those four groups together, the industry partners, startups, universities and also growers to do projects around it.

The third piece of that was the physical location, having an innovation facility where this work can happen. We can bring people out and educate them. We can do things in a low risk environment, and really get excited about the future of agriculture.

The fourth one was about upscaling the workforce knowing that we need to calibrate our systems from a university standpoint, but more importantly from a skillset standpoint in order to gear ourselves to the jobs of the future, especially as you bring this technology in.

The fifth one is about policy. Which is really the role of the private sector in the public sector, working together in a collaborative way to advance the technology.

That became our strategy—we put together a huge roadmap of things that we wanted to do.….and we never got the grant. But, we got a great plan that became the basis of how we started to engage with our partners, and we just started doing the plan even though we weren't funded with it.

We created the first ever North Dakota code school, called Emerging Digital Academy. And what this is designed for was to bring more students into computer science.

We did a study here, in our local region, that there are over 1000 open software development jobs. And the reality is, for every job that's posted, there's probably three or four that are behind that. So it was probably close to 5,000. The universities within our region were only producing about 200 students per year.

And so, that gap is getting larger. If we didn't address it or help address that, we would contain ourselves in terms of our ability to create this startup ecosystem.

The Emerging Digital Academy was launched in 2020, and we've now had three years of operations— I think we're in our ninth cohort. We've had over 60 students graduate through the program, and they're creating a great opportunity for themselves to fill that [industry] need.

Also, the students are significantly impacted. Their paycheck coming into the program is about $25,000, now for their first jobs, entry level is $60-70,000. That’s really significant.

We also recruited a couple business accelerators as well. Plug and Play created Ag. Tech Vertical here in Fargo. They're sourcing startups all over the world in order to be part of that program.

A lot of those startups we work with at Grand Farm

So, we’ve done over 700 projects. We have our partnership model that's designed around it. And as things start to evolve and take place, there's more and more interest coming into it, which is fantastic.

The big lesson was— we started with identifying the problem, and now we are solving the problem. As we started to solve problems, there was more and more interest, and more and more opportunities and partnerships, which was really a fascinating thing to see evolve.

Patricia: So, most of the farmers that I know, they obviously know how to run their high tech tractors and combines— they are trained on that. But, they either contract out for an infrared scan of their field or something similar, or they don't know how to operate their technology on their own. But now, it's pretty much a standard at a big Ag school that people are trained how to use these more tech-heavy field analysis tools.

So, in 20 to 30 years when those farmers eventually take over, farming is going to be a lot different. What do you think is going to be the biggest hurdle in that transition? And what do you think is the potential with food production?

Brian: One of the things that we did in our first year, is we sat down and listened to a whole series of farmer pain points. And, so we published our first ever Pain Point Report, which really listened to the farmers.

It was important to take that information and then get it to our industry partners and our startup partners. So they could have that insight.

Because, a lot of times, we see there's a disconnect between the technology and the end user, and agriculture is different from other industries in that the feedback loop isn’t as fast. It’s kind of constrained by the growing cycle. It's isolated, it's fragmented as well. What we want to do is create greater and greater feedback loops around that.

The insights that we started to get is: There's a lot of noise, especially around technology, in terms of the different claims that happen. And from a grower perspective, what they're looking for, is something that's simply going to improve their RIO. And if it works, if it can be demonstrated, they will incorporate it, but it takes a while for that adoption of technology to happen.

By the time it gets to the grower, it has to be really, really verified, trusted. And you can demonstrate that through what a lot of organizations that we work with, especially from the technology standpoint, that is probably the biggest barrier—just to make that connection between that technology and the impact it makes with the grower.

That's why the farm is so important, that's where all these things come together, they can see it, they can understand it. It’s not in a pamphlet, it’s not in a publication. It's something where you can kind of ‘kick the tires’ see and understand what that looks like.

So, I think the biggest challenge that I see is the adoption of technology, because the technology doesn't always address a specific pain point that the growers are looking for.

Patricia: I have a couple topsoil specific questions, because in Iowa it's been a really big point of tension, that we've lost a really significant part of our topsoil over the last 20 years just due to farming practices with soybeans and ethanol corn. So is that something that you're hearing a lot and people are actively looking for solutions for?

Brian: Yeah, and that's where when we talk about the projects that we put out there this year, North Dakota State University is really heavily invested in research around that. Here, the river valley topsoil is important because it’s a differentiator between us and other regions. And so there's been a lot of research around practices, you know, remediation on the fields as well.

So, a lot of that research is happening, and what we see through building those projects is how these practices can impact yields in home and farming– maybe to reduce impact and things like that.

To be able to take that research and bring it into the supply chain is beautiful.

Going back to like that first project, Harvest Trace, if you can start to connect the consumer with the grower, if they're an incentivized grower, honest with the consumer, you know, practices or what they're interested in, you could start to asset value back onto the grower in the example soybeans, the Asian market, the European market, the consumers having a lot of requirements in terms of where the species is being grown, you know, what's being done to it in this to give our farmers an advantage.

Because, if you compare our farming practices with other markets, other organizations, we already have a lot of these things in place—where in other parts of the world maybe not so much. And then once the countries started incentivizing around that, it was a really strong position.

Patricia: Thoughts on affording a population of one billion in the U.S. in the future?

Brian: I think a lot of the input costs, the resources that go into it, need to be more efficient to be able to really do simply do more with less resources. And that's where technology can come into play. We can be much more targeted with what we do.

You can be much more precise about what you put onto a field. You can also understand cause and effect in a much more clear way, especially as datasets become more robust as well.

That’s what I get excited about- how data sensors, and all these things become interconnected to make better insights and decisions..That will help the grower become more efficient.

When we first started [Grand Farm] we talked about a fully autonomous farm. And, while there's technology that's out there in which you could actually demonstrate that, it's not going to be adopted because there really isn’t a need for it. Right?

The need is around efficiency. And if autonomous systems will create more efficiency, that's where that adoption will take place.

But I get more excited about some of the mapping that's out there, the data flows to satellites, you know, these companies that are really, really targeting.

Rather than a peanut butter approach that that that a lot of growers have, you can be much more targeted within that. That will reduce the amount of input costs that you have.

Patricia: That's what I've heard from some vineyards in California that have within meters of each other different grapes, precision agriculture has been really helpful for them.

Brian: So, that’s a great example, because vineyards in California, the fields in Georgia, what's happened in Brazil, what's happened in North Dakota, there's a lot of technology, but that technology needs to have a local application. And so that local integration is one of the things that we're doing with Grand Farm.

We want to create a network across the globe in which we can take these technologies and see if something that is effective in the vineyards can be applied into a row crop.

Just like something in a row crop can be applied in a cotton field.

And that's where the fragmentation of the industry is oftentimes strained by the geographic boundaries, and the growing seasons and where you can actually grow within that.

But technology, for the most part, can be agnostic. It can go into all these different areas. If we can have people and organizations that are closest to the pain points matched with technology, then that technology can be used in a broader application.

Patricia: What do you make of the interest in vertical farms in more urban areas?

Brian: So, my insight comes from one of our partners, Eden Grow Systems. How we got connected with them was through our space ag conference. They were developing vertical farm technology that was going into basically the International Space Station, and some of the work that's happening with that. And what has been interesting with that, is that it’s starting to address some of the food deserts that are out there.

The use cases that they have are inner cities, where it might be hard to get fresh fruits and produce, they also consider their system as a living refrigerator. So a restaurant could grow its own lettuce.

So, how they describe it is democratizing the food systems. What's been interesting is, over the last couple of years, with some of the challenges with food security and supply chain issues, you start to start to create some capabilities that are outside of these larger [suppliers].

Patricia: Yeah, that's something that I've noticed, too. Also for better or worse, I think apocalypse movies and then COVID…people noticed that they didn't know how to do basic things that people like a couple of generations before and knew how to do.

Brian: And it will be interesting because, you know, 120 years ago, literally 95% of the population was tied into agriculture in a very direct way, whether directly producing or supporting, you know, and now I think it's just the 2% right?

And over that time, people have become really disconnected with their food sources. You just go to the grocery store and you see things and you know, if there's one industry in the whole world that's not going to get disrupted, it is going to be food. Everyone’s going to need to have that.

At least in our region, those systems are important, because our livelihood is dependent upon it. And more than that security system is, you know, really almost national security.

Patricia: We've seen more small organic farms and a renewed interest in the organic farm movement. Do you think that there will be more farmers? When I say a farmer, just a person responsible for a particular parcel of land, do you think they'll be more farmers or less farmers?

Brian: There’s an organization out of the UK called Harper Adams and they have a project called, “Hands Free Hectors.” One of the things that they do is involve economists in their studies. My opinion is kind of informed by them, because farming in the UK is much different—it’s much smaller.

Those economists have described that the barriers to entry are going to come down.

You're going to see a lot more nontraditional farmers moving into the field. Take our community, for example, we have a pretty strong new-American community.

They're starting to farm a small acre of land, create a lot of value, especially as they bring in their own crops. They're able to sell to markets, to restaurants. So, there's a lot of interesting new-American type of activity here.

One organization, called New Roots, is now bringing the African eggplant into the market. They sell eggplant to restaurants in Minneapolis, Chicago and around the region. It has created a whole new market because agriculture on a small scale is much more targeted.

Patricia: I’ve heard of a Thai place in D.C. that keeps their own garden for specific foods.

Brian: So it could very well change the food supply and cater to a lot of different tastes.

Patricia: Is there anything else important that you think I should know about the future of farming?

Brian: Our primary thesis on the Grant Farm is the ecosystem — that's what we want to do. We want to build as many partners and then bring them together. We want to create this feedback loop, because building work for more partners to create projects is, really, what excites me.

We have the privilege of seeing all these dreams and their different insights, the different pain points, listening to them, and then building projects.

In order to advance technology, and advance in the world, you need to have connections to these networks and partnerships.

Check out this related Mercatus Research: