Highlights:

"Without innovation and competition, the current macroeconomic environment facing the agricultural industry is a threat to rural life in America, the values and principles of property ownership, the sustainability of small family businesses, and the prevalence of agricultural entrepreneurship."

"An agTech pilot program resembles the regulatory sandbox model that has already been adopted across numerous states, such as Utah, Arizona, and North Carolina. Regulatory sandboxes allow startups and firms to test innovative ideas with real consumers under a regulator’s oversight."

"Considering that the vast majority (98%) of American farms are small family businesses, it is unusual that so few large corporations continue to dominate the agricultural industry. It is worth exploring whether.. adoption of a DAO (decentralized autonomous organization) enabled collective governance model could strengthen the power of [small farms]."

Check out the full piece below!Achieve Agricultural Abundance by Challenging the Status Quo

By Agnes Gambill West

To achieve the goal of agricultural abundance, bold experimentation, increased competition, and innovation are required. This essay presents three examples of how policy and technology, including those related to distributed ledgers and decentralized finance, may influence a path to agricultural abundance and increased property ownership in the United States.

U.S. Farming is Approaching a Tipping Point

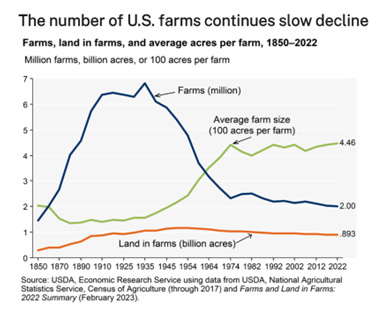

Agricultural abundance may seem like a hazy, distant vision given the macroeconomic conditions surrounding the farming industry in America. For example, the number of farms in America has dropped a staggering 70% since 1935, and as of 2022, only 2.0 million farms remained. Over the next 15 years, this number is expected to drop even further as aging farmers retire, debt obligations rise for small family farm owners, more non-farm jobs become available, small family farms are replaced with runaway, low-density urban sprawl, and the next generation of farmers experiences financial and regulatory barriers to entry.

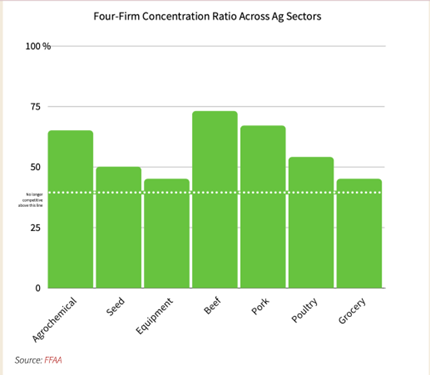

Agricultural markets are also thinning due to an increase in concentration of companies in many sectors of the agri-food ecosystem, including food processing, retail grocery markets, farm equipment sales, agrochemicals, and the seed market. For example, only four companies represent 73% of beef processing in America. However, market concentration seems to be more obvious in certain agricultural sectors than others. Research also suggests that the existing empirical evidence in the academic literature to support the hypothesis of a widespread problem of power buyer in agricultural product markets may be incomplete or may focus too narrowly on markets where problems are less pronounced.

On the one hand, concentration and consolidation may be a product of greater efficiencies, economies of scale, and productivity growth; but in certain instances, high concentration and consolidation has led to negative outcomes. For example, the US dairy industry has seen a sharp decline in small dairy farms because small farms are unable to compete with larger farms on pricing, exporting, and cost.

While larger farms are neither villains nor heroes, the effect of firm concentration does transform the competitive landscape of the agri-food industry in the United States. Without innovation and competition, the current macroeconomic environment facing the agricultural industry is a threat to rural life in America, the values and principles of property ownership, the sustainability of small family businesses, and the prevalence of agricultural entrepreneurship.

Blockchain Technology and Policy May Present Solutions

While many scholars, think tanks, and nonprofits have opined with a diversity of viewpoints on how to solve the current competition and innovation problems facing the agriculture and food industry, this essay presents three new concepts for consideration. Blockchain technology and agriculture may seem like strange bedfellows, but this technology has been quietly transforming the food industry, especially when it comes to supply chain management. For example, major food companies, such as Bumble Bee Foods and Kraft Heinz, are currently using blockchains to trace contamination and food borne illness, which has led to faster response times for informing citizens about possible health risks and product recalls.

Companies are also turning to blockchain technology to meet regulatory requirements. For example, the passage of the Food Safety Modernization Act (FDMA) establishes requirements for food tracing and recordkeeping, and one of the four goals of the FDA’s New Era of Food Safety blueprint focuses specifically on tech-enabled traceability. At the same time, the FDA is exploring entrepreneurial initiatives, such as the Traceability Challenge, that inspire the development of low and no-cost technology solutions to traceability issues. One reason for such an initiative is because the FDA wants to encourage voluntary adoption of tracing technologies in a scalable, cost-effective way for firms of all sizes. In other words, price should not be an impediment for firms to adopt new blockchain-enabled tracing systems. The FDA’s Traceability Challenge resulted in 12 winning teams that devised technology solutions for end-to-end traceability

In addition to supply chain management and product traceability, blockchain and decentralized finance can also play a role in agricultural financing and the formation of digital collectives that support local and regional agricultural communities. Because these use cases are considered novel, there is a need for greater experimentation, not only with the development of technologies with specific applications to the agrifood industry but also the broader adoption of new technologies and business models that challenge the industry’s status quo.

1. The Innovative Agricultural Technology Act

Legislative developments are underway to encourage experimentation with new technologies and innovation in the agriculture industry. For example, in October 2022, U.S. Senators Lummis and Blackburn introduced the Innovative Agriculture Technology Act, which would require the Secretary of Agriculture to establish an AgTech pilot program so that farmers, entrepreneurs, and government agencies can work together to encourage the creation of emerging agricultural equipment and technologies.

The proposed AgTech pilot program resembles the regulatory sandbox model that has already been adopted across numerous states, such as Utah, Arizona, and North Carolina. Regulatory sandboxes allow startups and firms to test innovative ideas with real consumers under a regulator’s oversight. The benefit of sandboxes is that companies would be able to test their ideas or products in the market for a limited time period without obtaining required authorizations or licenses from regulatory agencies, saving those companies time and money that would otherwise be spent on expensive regulatory compliance and legal fees. Such expenses are especially risky for startups that have untested business models and limited funding. Regulatory sandboxes may be particularly beneficial to heavily regulated sectors of the economy, such as the agriculture and food industries, where regulations are overly burdensome or slow to adapt to more efficient models of oversight given the changes presented by technological advancements.

One example of inefficient or counterproductive regulation in the agriculture industry is a requirement under California law that self-driving tractors have an operator stationed in the vehicle, which can eliminate the benefits of automated farming technology. Another example is a Mississippi law that requires drone operators to have an airplane pilot’s license. Agricultural drones are currently used in precision agriculture to apply spot treatments for pesticides and fertilizer, thereby reducing agricultural runoff and chemical drift, and can also be used in land imaging, surveying topography and boundaries, and livestock monitoring and counting. However, these innovative uses are out of reach for Mississippi farmers who cannot comply with this regulation.

The proposed AgTech pilot program is unique because it would be implemented at the federal level, and participating entrepreneurs would have access to consultations with the Secretary of Labor, the Secretary of Transportation, the Administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, and the Federal Communications Commission, as well as any applicable State agency. Some of the technologies highlighted in the bill include internet of things (IoT) technologies, Global Positioning System guidance, distributed ledger applications for tracing and sourcing, financial technology products and services for agricultural credit and loan opportunities, and non-fungible digital assets. The AgTech pilot program may become a driver of innovation where regulators play a role in lowering regulatory barriers and supporting innovation, experimentation, and entrepreneurial activity.

Distributed Ledgers, Decentralized Finance (DeFi), and Agricultural Finance

While new technologies may lead to greater efficiencies in farming and agricultural abundance, adoption of these technologies among industry participants takes time and depends on how well farmers trust the efficacy of the technology to produce returns on their investments. Education and experimentation with new use cases can accelerate endorsement and uptake of the most advantageous technologies while cutting through the noise of others that simply distract.

Another unique aspect of the proposed Innovative Agriculture Technology Act is the bill’s mandate that the Secretary of Agriculture establish an educational program for agricultural producers on the benefits of implementing distributed ledger technology in agricultural production, distribution, and sales. The bill also mandates the Secretary of Agriculture to conduct a study in coordination with other federal agencies that identifies potential applications for distributed ledger technology in agricultural operations.

Potential use cases that the Innovative Agriculture Technology bill highlights for further exploration include the tracing of products, monitoring of farm conditions, maintaining of records related to equipment usage, verifying and certifying data, ordering supplies, and using asset exchange tools that facilitate payments for products and equipment. These legislative policy goals will lay the groundwork for exploration of new ideas, experimentation, and innovation across various segments of the agricultural economy in America.

One existing use case, built by Dimitra Incorporated, is a decentralized lending and insurance platform for small farm owners that has been developed and tested by governments and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) across the world. The Dimitra platform is built on blockchain technology and incorporates IoT devices, satellite and drone imagery, machine learning, and mobile technology to provide micro-credit financing, farm and livestock insurance, genetic data tracking to increase livestock productivity, tools that improve efficiencies in logistics and exports, and soil assessment and remediation. The company has launched projects in Nepal, India, Brazil, Uganda, and Bangladesh, and worked with millions of small farm owners across the world.

One of the benefits that Dimitra’s decentralized platform offers is the ability to leverage blockchain and other technologies to aggregate information related to crops, livestock, soil conditions, and weather. This information is otherwise fragmented, inefficiently circulated, or poorly documented. The Dimitra platform enables large groups of small farmers to collect, manage, and analyze aggregate data that will inform the group’s collective decision-making while strengthening their community support networks. Access to these benefits is important because many farmers in these countries cannot afford to move into higher-scale production on their own.

In America, Dimitra’s decentralized financial tools have the potential to reach small farmers and small community farming networks, especially those that need loan financing for startup farms or those that operate in segments of the agricultural economy where there is scant competition for producers to receive improved pricing for their goods and services. Dimitra’s use of decentralized finance and complementary technologies is illustrative of how small farm owners may be able to obtain financing and insurance through alternative channels, thereby increasing the odds of sustainable farm longevity and increased rates of property ownership. Shared information networks, facilitated through decentralized technologies, may also give community farming groups an enhanced edge over the major power players in the nearly monopolized state of America’s agricultural industry, thereby enhancing competition.

Decentralized Autonomous Organizations, Geographical Indications, and Sustainable Food Systems

The use of decentralized finance (DeFi) in third world countries to shape and strengthen community farming networks is a reminder of how collective governance can play a valuable role in creating sustainable food systems. One concept that deserves further exploration and experimentation is how decentralized autonomous organizations (DAOs) can augment digital collective governance for a new wave of tech-enabled agricultural production for a decentralized network of small farms.

Research shows that collective governance in farming is more prevalent worldwide than in America for various reasons. Some countries have complex environmental ecosystems, like semi-arid regions in Africa, that make it difficult to develop product markets and sustain careful environmental management of the region. As a result, small farm owners that are dispersed and operating within these challenging ecosystems benefit from working together, building networks, and sharing information.

Other countries rely on collective governance to manage geographical indications, a type of trademark that is used on goods from a particular geographic region and that possess qualities or a reputation that are due to that special location of origin. The use of geographical indications is popular in Europe, and these trademarks protect famous food and drink products, such as Roquefort cheese and Champagne, from unauthorized production. Collectives from these designated regions manage oversight of the use of the trademark and maintain quality control over the protected products. In America, some of Europe’s most famous geographical indications, like Gruyère cheese, have been under attack by advocacy groups over claims that such product names are not eligible for legal protection because of their existing common usage in society. These lawsuits and the fact that geographical indications are not well understood by the American public as an available, alternative type of trademark could explain why more goods are not protected by this legal mechanism.

The combined use of collective governance and geographical indications in agriculture has consistently led to positive economic development outcomes for groups, communities, and regions in rural areas around the world. Some of those outcomes include benefits to reputation building for a product or region, shared resources for marketing, sales, and distribution, pride in local communities, increase in quality of goods, improved information transparency that enables greater pricing power for producers, and collaborative opportunities with other stakeholders in the region. So, how do DAOs play a role in this framework?

DAOs are novel organizational models that exist predominantly in the virtual world and do not have a central governing body. All the members in the DAO share a common goal to act in the best interest of the entity, and decisions are made from the bottom-up. These organizational characteristics seem to uniquely complement the collective governance goals of agricultural collectives.

Considering that the vast majority (98%) of American farms are small family businesses, it is unusual that so few large corporations continue to dominate the agricultural industry. It is worth exploring whether the widespread or even localized adoption of a DAO-enabled collective governance model could strengthen the power of these fragmented, small farms and thereby introduce more competition in the system. While such a proposal seems highly experimental, agriculture-related DAOs do exist. For example, the Big Green DAO is an example of a DAO-entity engaged in collective governance for decentralizing grant-making for food and gardening organizations in America.

Because this area of research is underexplored, many questions remain. For example, what challenges to competition will the collective governance model of agricultural DAOs create? What risks might emerge from widespread formation of these collectives and how might those risks affect the overarching farming economy? How might agricultural DAOs transform rural life? Will agricultural DAOs lead to agricultural abundance, and how should we define abundance in that context?

Challenging the Status Quo

Achieving agricultural abundance is dependent on numerous factors, such as lowering regulatory barriers for farmers, encouraging policies that support the piloting of new technologies that may improve efficiencies in farming processes, and cultivating a culture of experimentation and entrepreneurship in rural America that leaves room for the discovery of novel applications of economic theories in the agricultural industry without the fear of failure or political disfavor.

Maintaining the status quo stands to be America’s biggest threat to innovation. Challenging that status quo begins with thinking outside the box, and new technologies, such as blockchain and decentralized finance, may serve as part of a nuanced solution that can influence a path to agricultural abundance and increased property ownership in the United States.

Agnes Gambill West is a Visiting Senior Research Fellow at the Mercatus Center at George Mason University. Her latest work can be found here.

Further Reading:

Creating Sustainable Food Systems with Trademarks and Technology, by Agnes Gambill West.

Innovation and Stagnation: Ethanol and the Renewable Fuel Standard, by Arthur R. Wardle.

Cultivating The Farm-Startup Ecosystem: An Interview with Farm Entrepreneur Brian Caroll, by Patricia Patnode.