A significant portion of American school children eat two meals at school during the academic year. Additionally, many children participate in after-school programs run by non-profits, such as the Boys and Girls Club or YMCA, which often serve kids dinner and snacks.

“Just before the pandemic in 2020, nearly 77% of all students qualified for free or reduced price meals. Last year, a staggering 96% of all students qualified for free or reduced price lunches,” Juliana points out.

For many students whose parents are either unwilling or unable to feed them, it is highly likely that all of their meals are provided by schools or grant-funded after-school programs during the academic year.

Considering the significant influence the government has over children's diets and the growing investment of taxpayer funds in nutrition education and research, it is perplexing why children's health has continued to deteriorate.

To further investigate this matter, Juliana Sweeney, a teacher herself, spoke with cafeteria workers, examined school lunch reports, and provided an overview of key issues with our current lunch program.

Some highlights from her essay:

“Your tax dollars are being spent spent on Lunchables for nutritionally deficient children across the country—recommended by experts at the United States Department of Agriculture and funded by the budget of your senators and congressmen in Washington, D.C.”

“The government has recommendations and guidelines for each of these variables, but none are as specific, far-reaching, and consequential as those mandated by school nutrition programs. Because so many of our children rely on federally-funded and regulated meals each day, the quality of the nutrition regulations must be considered.”

“We need to dramatically change our children’s relationship with food at school.”

Key Takeaway: Considering the foundational role of food in daily life and its direct impact on health and well-being, schools should prioritize nutritional education. This will enable students to cultivate healthy habits that can be sustained beyond graduation.

School Lunches are Failing our Children

By Juliana Sweeny

Lunchables are now an acceptable free school-lunch meal according to supposedly improved guidance from the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA).

In spite of increased federal and state regulations on school nutrition, childhood health markers continue to decline across the United States. Although school lunches do not account for all problematic health outcomes for children, the program sets an example for how poorly the government regulates individual needs— and how rigid guidelines may actually contribute to the larger problem at hand. Simply put, school lunches are failing our children and it’s time to take corrective action.

The continuous expansion of school lunch programs in the United States

School lunch programs are not new— although school lunch services existed prior to the 1940s, the National School Lunch Act was signed by Harry Truman on June 4, 1946 and authorized the creation of the first National School Lunch Program (NSLP). Although the law has been amended various times, the program still exists and provides low-cost or free lunches to children at public and nonprofit private schools and is overseen by the Food and Nutrition Services (FNS) division of the USDA.

Just 20 years after the establishment of the NSLP, Lyndon Johnson signed the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 which created a similar program for free or low-cost breakfasts. The same law established the authorization of the Special Milk Program which provides free or low-cost milk to schools that do not participate in other nutrition meal service programs. Two years later, the Summer Food Service Program was established to provide assistance for schools to provide meals for children when classes are not in session. In 1968, the program was permanently renamed the Child and Adult Care Food Program and provides assistance for meals at both childhood educational facilities and also for homeless shelters and adult day care centers.

Recent amendments to the aforementioned programs include two acts from 2009 and 2010: The Agriculture, Rural Development, Food and Drug Administration, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act and the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act, respectively. Collectively, these two pieces of legislation authorized more grants for the improvement of health and wellness projects in childcare settings and also expanded after-school meal programs for at-risk children in all 50 states.

Free Lunch…

In 1969, shortly after the establishment of many federally-funded meal programs, only 15.1% of all students qualified for free or reduced price lunches in the United States. Just before the pandemic in 2020, nearly 77% of all students qualified for free or reduced price meals. Last year, a staggering 96% of all students qualified for free or reduced price lunches.

Each day, on average, over 30 million students in the United States participate in school lunch programs, which amounts to nearly 50 billion meals across the United States each year. That’s a lot of student meals based on constantly shifting nutritional guidelines created by the USDA—and a lot of tax dollars to finance free lunches.

…comes at a steep cost

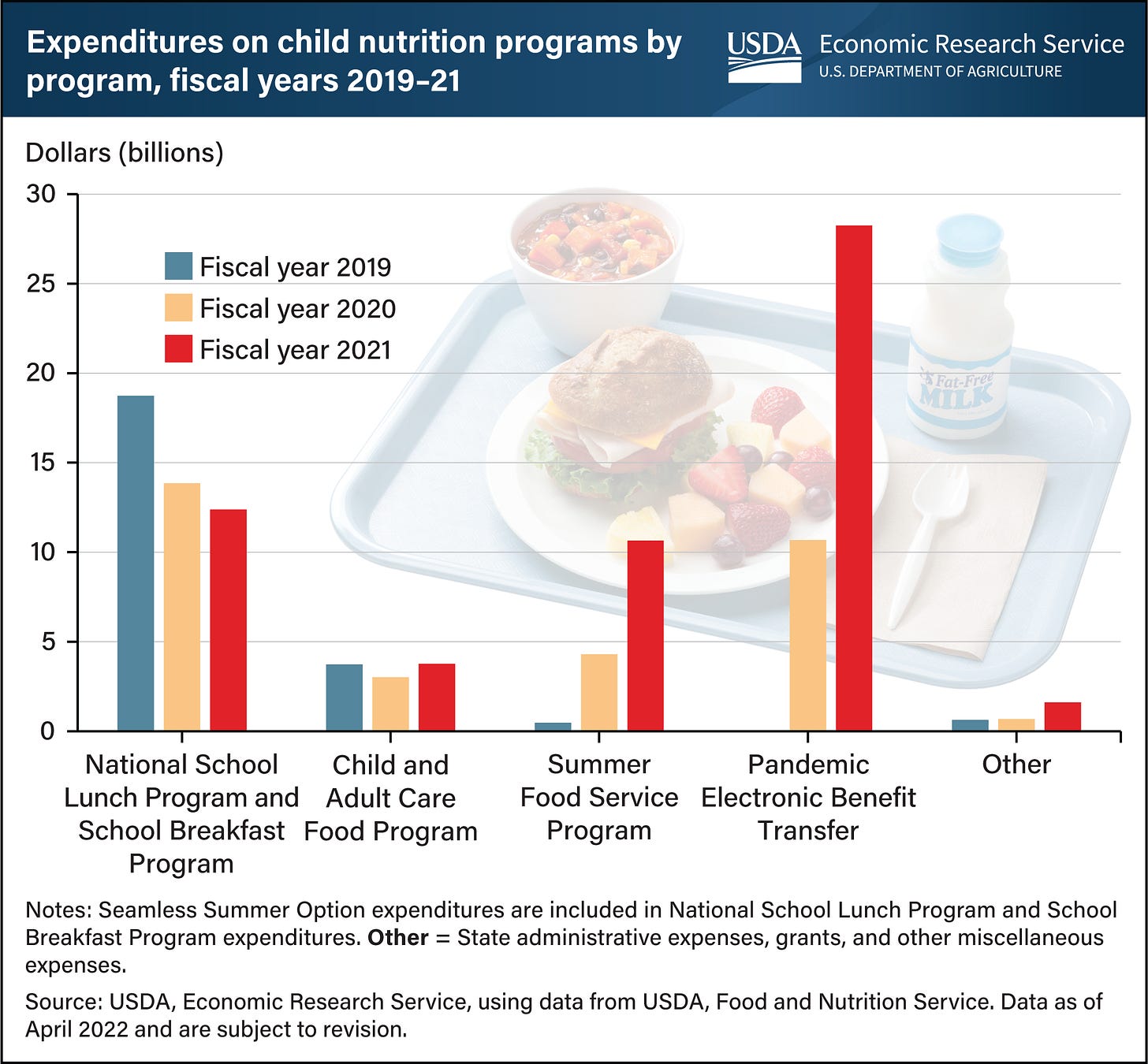

The NSLP is the most expensive child nutrition program, according to the USDA.

The approved federal budget set forth by Congress for Fiscal Year 2023 (FY23) set aside $1.7 trillion dollars for total discretionary spending—the very top of their report notes that $28.5 billion tax-payer dollars are allotted for child nutrition programs—nearly $2 billion more than in FY22. According to their numbers, this will support the 5.2 billion school lunches and snacks during the school year. The bill provided nearly $50 million for similar summer and breakfast programs as well.

Legislation for the establishment and maintenance of federally-funded meal programs have only expanded in the last 60 years. Similarly, regulations on the subject have only grown more and more complex. Funding and research continue to increase and yet, results on their impact are questionable at best. School chefs and cafeteria workers argue that the regulations are too difficult to maintain. Chefs and child health experts even point out that standards could be more harmful than helpful, contributing to the overall decline in national childhood health over the last 60 years.

The challenges of school chefs

Creating meals for hundreds or thousands of students, five days a week, is a strenuous task in and of itself. As regulations change from year to year, school cafeteria workers are entrusted with an even more daunting task to create new mega-recipes that follow subjective guidelines from the various USDA programs.

Making school meals that comply with the latest guidelines is a moving target, nearly impossible to hit.

“During Michelle Obama’s time (of influence), our guidelines were very strict. (Schools) came down hard in order to be refunded by the government for children’s food programs,” said Naomi Bien, a former public school cafeteria worker from Missouri.

“The COVID-19 pandemic policies created even more problems for kitchen staff— ‘It was crazy. We changed so many protocols and were making meals to be picked up by families and even delivered to homes… All of this was supported and paid for by the government, but it put a lot of pressure and extra work on the kitchens,” said Bien.

One challenge not entirely addressed by guidelines is the growing prevalence of dietary restrictions and food allergies. “From my perspective, one of the hardest things was having options for a growing number of students with food allergies such as gluten free or vegetarian,” said Heidy Cowell, a former private school cafeteria worker from southern Arizona.”

As the challenges mount and restrictions continue to change, more schools opt for third-party services to run food-programs. Although this might ease overhead costs for school districts and private schools, students will be given less and less options to fit specific dietary needs.

If guidelines were universally or even majoritarily supported, perhaps third-party lunch distributors would be a good and reasonable solution for problems faced by school cafeterias. But, unsurprisingly, the guidelines are not based solely on the nutritional needs of students, but on the wishes of Big Ag lobbyists and legislators who need to send “pork” back to their districts. If student health showed improvement over the last decades of increased spending, continued regulations and updated guidelines would be desirable. But the opposite is true: childhood health continues to decline at alarming rates.

Children are becoming more and more sick

Food regulations continue to multiply and spending on childhood nutrition skyrockets, but children’s health statistics are plummeting in the United States. Over the last 60 years, obesity is just one of many health markers which indicates the rapid decline of childhood health in the United States. Although the stigma surrounding obesity has shifted in recent years, doctors from the American Academy of Pediatrics agree: “obesity is a complex, chronic disease that requires medical attention.”

Childhood obesity shouldn’t be portrayed positively or ignored by influential figures. Chronic illnesses such as obesity set our children up for long-term health complications, cost millions of tax-payer dollars and take years off of life expectancy. Obesity is not something to take lightly, and nutritional standards are part of the massive problem.

The percentage of obese children in the United States has quadrupled in the last 50 years: 5.2% of all children were obese in 1974, compared to 19.3% in 2018. Of our 73 million children and adolescents, 14 million are classified as obese.

The degree to which parental responsibility is the cause for childhood obesity is up for debate, especially considering the emerging science on genetic predisposition, but the harmful effects are not. There are many lifestyle factors which could be addressed by the population at large: movement, nutrition, sleep, medications and the environment, to name a few.

The government has recommendations and guidelines for each of these variables, but none are as specific, far-reaching, and consequential as those mandated by school nutrition programs. Because so many of our children rely on federally-funded and regulated meals each day, the quality of the nutrition regulations must be considered.

We need to dramatically change our children’s relationship with food at school.

Although schools cannot provide dozens of options during the lunch hour, schools should have the freedom to offer variety for their students, rather than be forced to follow subsidized political nutrition guidelines. After all, nearly 96% of all school children qualify for such politicized meals each day.

Political food guidelines → faulty nutrition

Food guidelines reflect the whims of both elected leaders and faceless bureaucrats in Washington, D.C. The USDA has some degree of control over every level of food production and consumption in the United States: from how a crop is grown, to how much can be planted or harvested of certain foods, to the substances used to fertilize or feed crops, to the way in which consumer foods are packaged, to where commodities can be sold, all the way to the foods millions of students should eat for lunch… isn’t there a conflict of interest here?

Some regulations are good and desirable (remember the meat-packing debacle that led to the Meat Inspection Act from high school history class?). While limited governmental oversight protects American consumers from gross negligence, increased regulation at all levels of industry breeds secrecy and keeps the market from responding with innovative, competitive solutions.

Bad history. Bad guidelines. Bad outcomes.

Your tax dollars are being spent spent on lunchables for nutritionally deficient children across the country—recommended by experts at the United States Department of Agriculture and funded by the budget of your senators and congressmen in Washington, D.C.

Increased government intervention and spending so far has not solved the crisis, and children’s health has only gotten worse. Improving health outcomes for children requires a culture change that laws and spending alone cannot fix. Different solutions should be considered; whether it be school independence to address nutritional differences, or a movement against the politicization of nutritional guidelines altogether— Americans must address the crisis at hand.

Although the USDA should certainly update its guidelines to reflect best outcomes for children (rather than progressive wish-list items), they probably won’t. School boards need to take the worsening health of students seriously and improve school meals and nutrition education.

Juliana Sweeny is a high school teacher, volleyball coach, and athletic director in Loudoun County, Virginia.

Subscribe to Farming Abundance for Juliana’s “Part 2: The Solution” which will go live next week!

Further Reading:

SNAP can improve nutrition, help farmers, and support the environment By Angela Rachidi for Farming Abundance

The Conservative Case for SNAP Restrictions by Angela Rachidi for AEI.

Phony Demand and Underpopulation: Problems Plaguing American Farmers By Matthew Yglesias for Farming Abundance

Call Out Crony Crops by Patricia Patnode for Farming Abundance

“Oh SNAP!” That’s So Not Working by Patricia Patnode for Farming Abundance